Moving molars through the maxillary sinus... myth or reality?

I am writing this blog just after the SAS The Next Level event we held in Madrid. As Dani says, we are still with a bit of an emotional hangover. Before going into detail on the subject of the blog, I would like to thank again the great welcome and support of all the doctors who accompany us and make it possible that day after day we continue to share with you our particular vision of invisible orthodontics, with no secrets or secrets. In this course we talked about how to solve cases of included canines and extractions with aligners, learning how to make a coherent and logical use of CBCT in our digital planning.

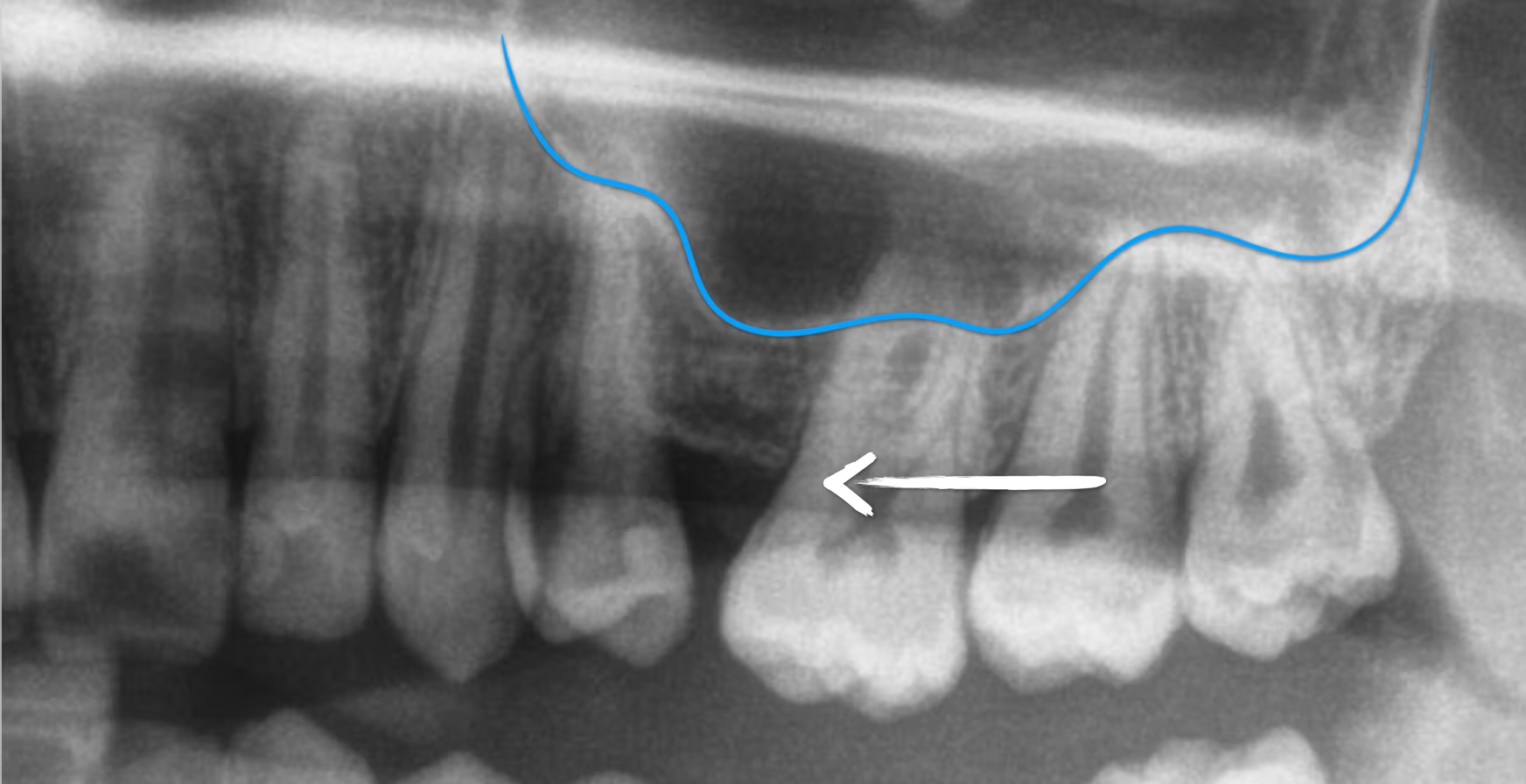

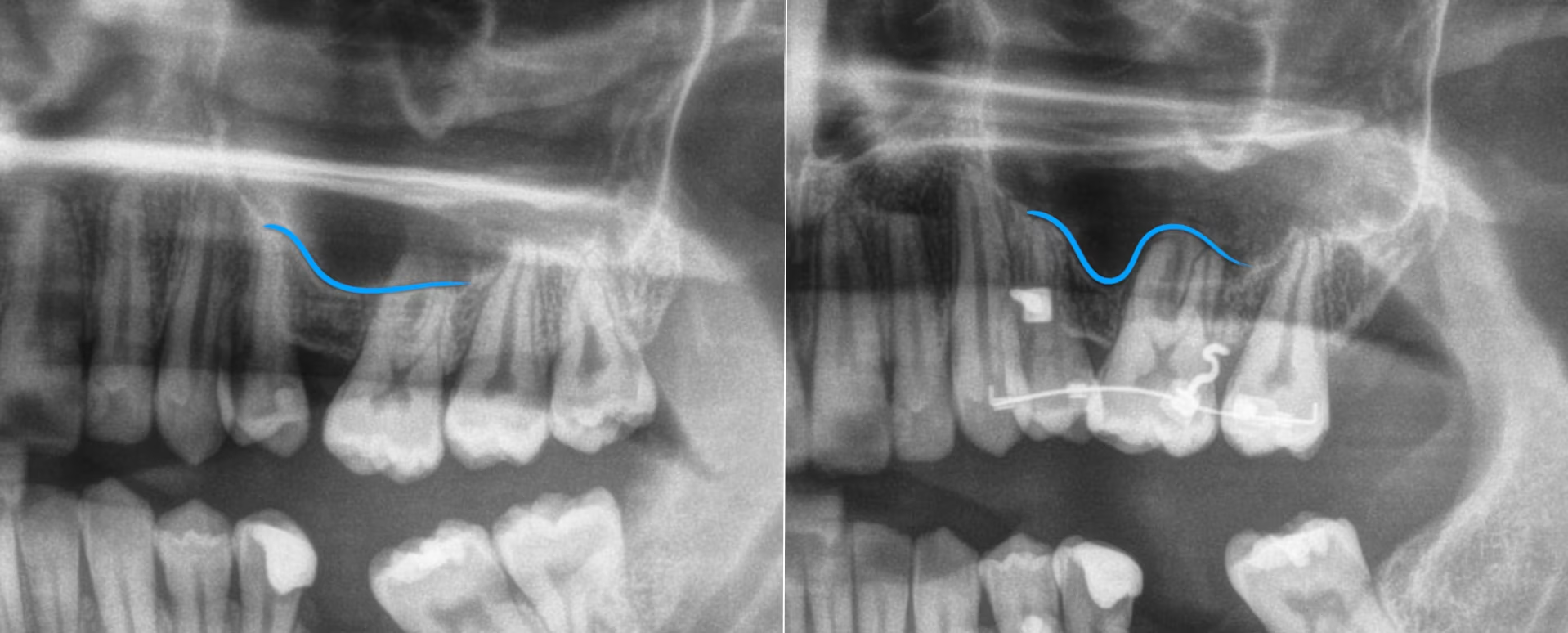

In these talks, one of the topics we dealt with was the movement of teeth through the maxillary sinus. When we have a patient with spaces in the upper arch, we may think that, if the sinus is very pneumatic, we will not be able to close them because of the inability of the roots to move through it. Numerous articles have shown that this old belief is not entirely correct.

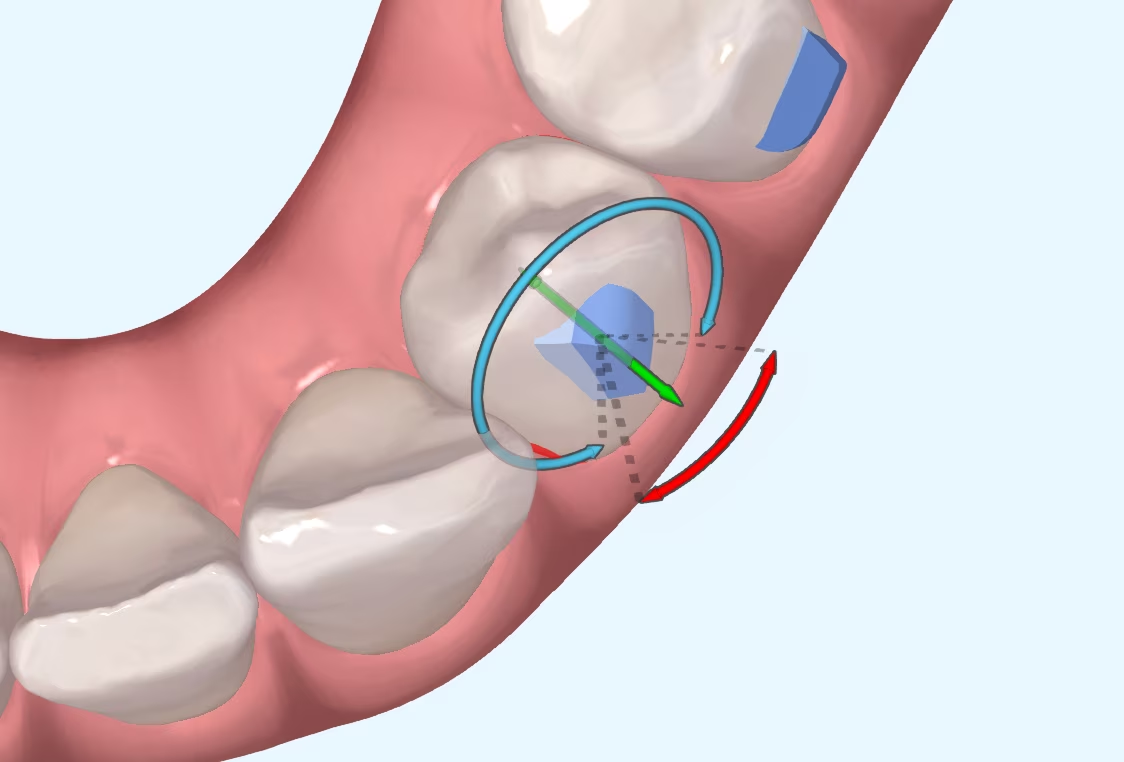

Moving teeth, or rather moving roots through the maxillary sinus, is possible. However, as with any movement through cortical bone, it is going to be complicated and variable in nature, and is not without risk. If we choose to close a space in the upper arch (by mesialisation of molars, distalisation of premolars or a combination of both) and we have to face the sinus, the movement of the molars can be done in two ways: by inclination or by mass movement. If we are thinking of treating the patient with aligners, we will assume that the plastic will not be able to control the root. If we want to close the space by, for example, mass mesialisation of the molars, we will have to resort to auxiliary techniques, such as those shown in the picture to achieve this. Pretty? Believe me, it's not easy.

In the course we discussed whether such treatments are worthwhile, as the degree of uncertainty is high and the risk of not closing the space completely is also high. A systematic review on the subject reveals some interesting data:

- Moving premolar and molar roots through the sinus is possible, but the speed of movement will be highly variable. The speed can range from a maximum of 1 mm per month (rare) to speeds as low as 0.1 mm per month.

- In some patients, this movement can be beneficial because of the ability to "create" new bone in the apposition zone during the displacement of the teeth in the sagittal plane. Although it is a longer treatment, it can be beneficial if we need to increase the height of the bone to place implants in the upper arch.

- This movement requires high forces, between 200-250g. Despite this, no case has been observed in which the sinus membrane has been perforated; the cortex remains intact. Comparing the X-rays, it can be seen how the cortex somehow accompanies the root throughout its movement. This effect or phenomenon is different when compared to the consequences of expansion and pro-inclination movements on the vestibular cortex. At the moment, there are no studies that show vestibular cortices moving at the same rate as incisor or molar roots. The exact reason for this behaviour of the sinus cortical is unknown, but knowing that we are not going to perforate the membrane is reassuring.

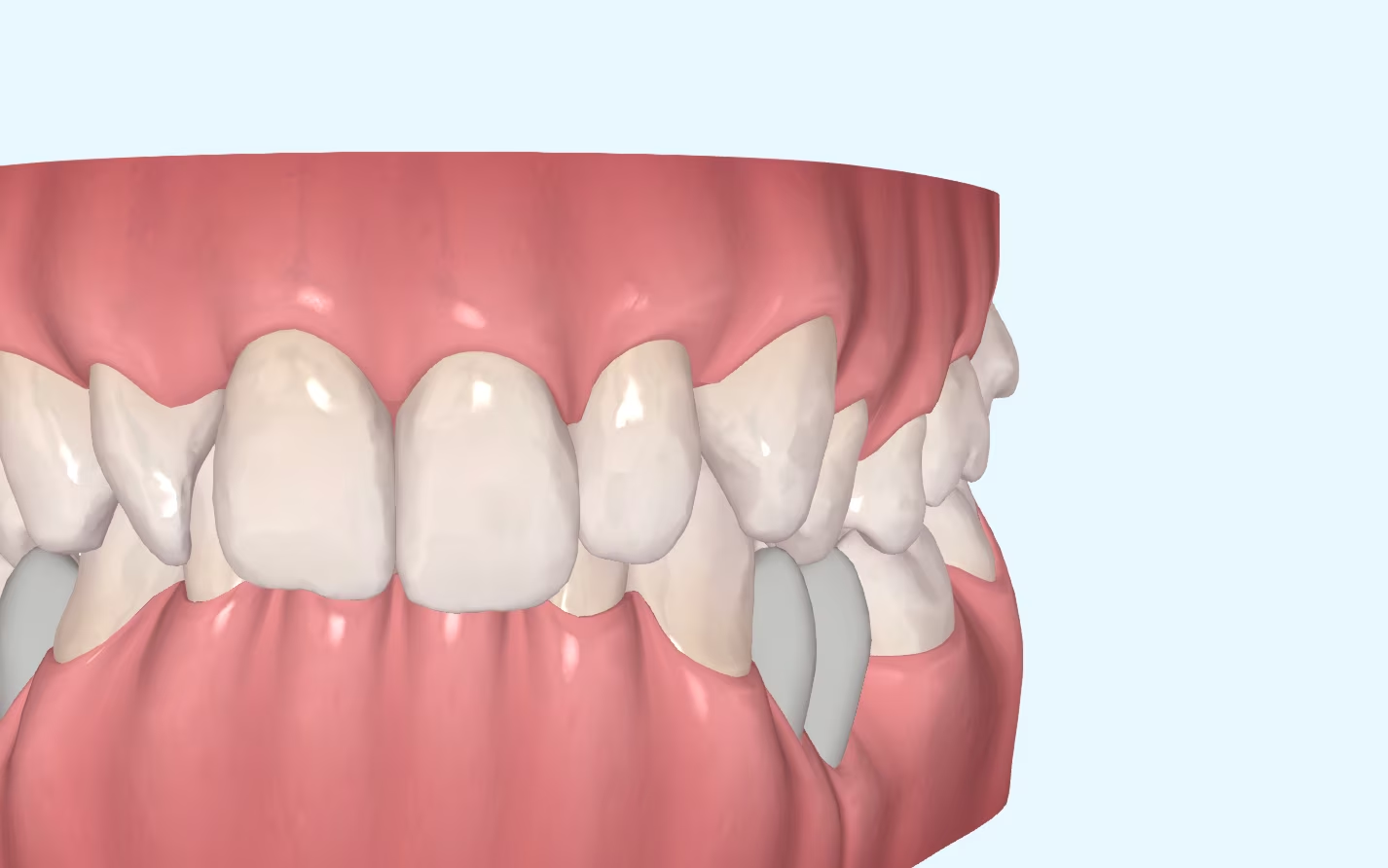

Reading this data, we can conclude that closing a space in a patient with pneumatised sinuses is going to be complex to achieve and to plan, as the speed of movement that we see in the ClinCheck or Approver will probably not be the same as the speed at which the teeth will move. Even if auxiliary techniques are used, movements can be stuck or delayed, so it is important to be cautious and to present the patient with all possible solutions and to be realistic about the treatment objectives. Just because it is possible to move roots through the sinus does not mean that it is suitable in all cases.

Sun et al. Knowledge of orthodontic tooth movement through the maxillary sinus: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health (2018) 18:91.

Share this post:

Other entries

Which attachments are better for premolar rotation?

I suppose many of you are familiar with the myth of Achilles, the Greek hero who was immersed as a child in the River Styx by his mother in order to make him

Has CBCT been a step forward in dentistry?

What is CBCT? CBCT is a medical imaging technique that uses a special type of computed tomography (CT) scan to obtain three-dimensional images.

Mastering the Overbite: Strategies and Challenges:

Challenges of Overbite In the more than 20 years that we have been working with invisible orthodontics, we have gone from considering some malocclusions "impossible" to daring to

Are we aware of what we are doing?

It is not a question to make us feel guilty. It is only a question that invites us to reflect, to think about the impact we can have in

MARPE: Is there an age limit for placement?

Introduction: Understanding Maxillary Compression Maxillary compression is a relatively common problem seen in our daily practice. This osseodental discrepancy that presents the